Data protection by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Pix4free

What is personal information? What is a Cookie Consent popup on a web page? What are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), the GDPR’s South African equivalent? This week’s post looks at recent legislation around personal information and how we need to consider protecting it when working with OER and open education practices.

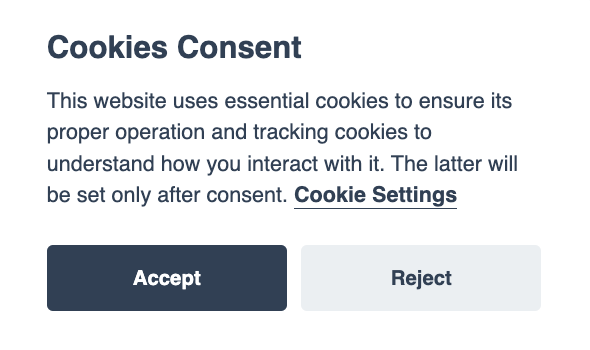

When you open a webpage, you may have noticed that there is often a pop-up on the page which asks if you accept the website recording your interactions with it. There are many different formats; this is the one we use on the OER Africa website:

Most websites use HTTP cookies (web cookies, browser cookies). These are small pieces of data created by a web server while a user is browsing a website, which are placed on the user's computer or other device (Source: Wikipedia). Cookies serve important functions, such as authenticating the user and storing sensitive information. If you click “Accept”, then cookies will be set on your device, whereas if you click “Reject”, you may not receive the full user experience on certain websites. ‘Tracking cookies’ collect long-term records of individuals’ browsing histories and can be used to target advertisements to individuals. This has led to concerns about invasion of privacy, resulting in countries and blocs of countries requiring ‘informed consent‘ from the user before data is captured. The European Union enacted the GDPR that requires users to ‘opt in‘ to their cookies being stored. Similar legislation has been legislated elsewhere, for example the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the US, and POPIA in South Africa. The African Union has called for the adoption of a common framework on the protection of data and at least six countries have adopted laws for the protection of their citizens (Daigle, 2021).

This short video explains how the GDPR works. Although it relates to Europe, data privacy laws in other countries work in similar ways.

How does this relate to OER?

As the name suggests, privacy and personal data protection legislation is intended to protect people from having their personal information accessed without their consent. There are two main ways in which personal data might be at risk when working with OER.

First, there is evidence that ransomware and related attacks target the education system, specifically school and university websites (Zdravkova, 2019) and that the attackers have accessed email addresses and other data from students and staff to mount the attacks. If you access a site that includes OER or open courseware, ideally you should be presented with a cookie consent form. You can then choose whether you allow yourself to be tracked and what data the website may use. For example, the UK-based Open University website includes a cookie consent popup on opening. While Khan Academy does not have one, it does have a page explaining its policy on cookies. Others, such as the MIT Open Courseware Repositoryand the South African Siyavula website (openly licensed school science and mathematics resources), do not show a popup on opening. Users need to be aware of the possible risks they face when using such webpages; their browsing history may be tracked. In the commercial world, unscrupulous companies sell user data to other companies for profit.

Second, many online activities require users not to be anonymous when working with OER. When creating an OER a person would normally provide their name and (possibly) their affiliation. In giving this information, users should be aware that the information can be shared widely. More importantly, if you are working with students, they need to be aware of their rights to informed consent. For example, if you are working with students on platforms such as learner forums, Twitter, Facebook, and Wikipedia, they should be aware that their data are being shared. Large companies usually list consent within their Terms of Use/Terms and Conditions, which can be very extensive, couched in legal language and are often not read by the user before being signed. We recommend that universities should adopt data consent policies for their students, and that academics and librarians should make students aware that their consent must be freely given, specific and unambiguous. Such consent may constrain existing practices, for example if an academic sets the writing of a Wikipedia article or a series of tweets as an assignment, the student cannot be forced to create a social media account in order to comply with the assignment.

In summary, with the rise of digital technologies (particularly smartphones) personal information of users can be easily accessed and tracked. If they register on a site, the information may include their browsing history, email address and any other details they have entered. People accessing and creating OER should be aware of the risks of allowing access to their personal information: OER repositories should consider including cookie consent popups, while data consent policies need to be made clear to all users.

References

- Daigle, B. (2021). Data Protection Laws in Africa: A Pan-African Survey and Noted Trends. Journal of International Commerce and Economics, February 2021. Retrieved from https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/journals/jice_africa_data_protection_laws.pdf

- van Valkenburg, W. (2018). GDPR and Open Education. Retrieved from http://www.e-learn.nl/2018/04/08/gdpr-and-open-education

- Zdravkova, K. (2019). Compliance of MOOCs and OERs with the new privacy and security EU regulations. 5th International Conference on Higher Education Advances. Retrieved from http://www.headconf.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/9063.pdf